At Permanent.org, we believe that preserving community stories should be accessible to all. In this guest blog post, we spotlight a recent Byte4Byte internship at The Peale in Baltimore, where University of Maryland graduate student Nicolas Lizarralde helped organize and add metadata to their Out of the Blocks oral history collection. His work not only helped make these powerful community voices more accessible, but also provided The Peale with a clearer path toward sustainable digital preservation. The post is written by both Heather Shelton, the Peale’s Digital Curator, and Nicolas.

Heather Shelton: At The Peale in Baltimore, community voices are at the heart of everything we do. Housed in the oldest purpose-built museum building in the United States—built in 1814 by artist and inventor Rembrandt Peale—The Peale has lived many lives. Over the centuries, it has been Baltimore’s City Hall, the first public high school for students of Color, a mattress factory, a sign shop, and for much of the 20th century, a municipal museum. After falling on hard times in the late 1990s and closing its doors, it took years of preservation work, vision, and community effort to bring The Peale back to life. In 2022, the building reopened not just as a museum, but as a platform: a community museum dedicated to elevating the voices, ideas, and creativity of Baltimoreans.

That mission began taking shape in 2016, when The Peale—then still in the process of restoration—started collecting stories through a collaboration with the MuseWeb Foundation. The project, Be Here: Baltimore, invited local storytellers to document the history and cultural life of their neighborhoods in their own words. Participants were given a small stipend and the freedom to tell stories that went beyond headlines and stereotypes, capturing a more honest and nuanced narrative of the city.

That early success launched a wave of story collecting. With support from the Smithsonian’s Museum on Main Street program, The Peale helped maintain and further develop the already successful Stories from Main Street iOS app. Launched back in 2011, this story recording tool allowed users to record their short responses to prompts like, “What does living in a small town teach you?” and “What recipes are passed down in your family?” The innovative part at the time was that there was little moderation.

There was certainly review of stories that were submitted, but there was no editorial judgement. All stories were valued equally, whether they were 10 seconds or 10 minutes, whether they covered a serious, thought-provoking topic or meandered on about cruising with friends on a Friday night. Even more revolutionary for a museum at that time, the content went live immediately. At one point, the Stories from Main Street app was a Top 25 educational pick in Apple’s App Store—offering users a simple, accessible way to record and share personal stories about their hometowns. Naturally, we piggybacked on the platform’s potential and used it to invite Baltimoreans to contribute. (We’re now using the WebApp version of that initial Stories from Main Street platform, accessed through The Peale’s website).

From there, our archive grew rapidly. Through partnerships with Maryland Humanities, Lexington Market, and the Town Creek Foundation, The Peale coordinated storytelling initiatives across the region, capturing hundreds more oral histories. The result: a rich, ever-growing archive of voices and experiences from across Baltimore. But with all that storytelling came a big challenge.

Like many small museums, we were trying to do more than our staff capacity reasonably allowed. We were managing events, exhibitions, communications—and now, an expanding digital archive of community stories. We had secured a low-cost DAMS (digital asset management system), but didn’t have the time to keep up with the pace of new content. We found ourselves asking: How do we make this process sustainable? How could we manage our growing collection in a way that didn’t require a dedicated archivist—or a custom-built system we couldn’t afford?

That’s when we discovered the Permanent Legacy Foundation, whose Byte4Byte program offered both free digital storage and the chance to host an intern to help us tackle our backlog. It was exactly the kind of practical, people-centered solution we needed: affordable, accessible, and easy to use without heavy onboarding.

In the section below, you’ll hear from Nicholas Lizarralde, a graduate student in the Library Science Program at the University of Maryland, College Park. Nicolas joined us in January 2025 to work directly with a specific collection—making sense of what we had, organizing it, and helping us imagine what a more sustainable archival process might look like for a museum like The Peale. Because we believe that preserving community stories shouldn’t just be a luxury for large institutions—it should be a shared responsibility we all can take part in.

Nicolas Lizarralde: The Peale’s Out of the Blocks collection (OOTB) is an online compilation named after and containing a series of interviews co-created by sound engineer/photographer Wendel Patrick and producer Aaron Henkin and aired on Baltimore’s WYPR radio station from 2015 to 2021. Said interviews are held with a wide sampling of Baltimore’s people of all colors, classes, and creeds on topics as profound as the meaning of life and as mundane as the realities of daily life and are set to bespoke music by Patrick as Henkin converses with his subjects. They represent Baltimore in a way tales of great generals and politicians fail to do so: they are stories of the common people.

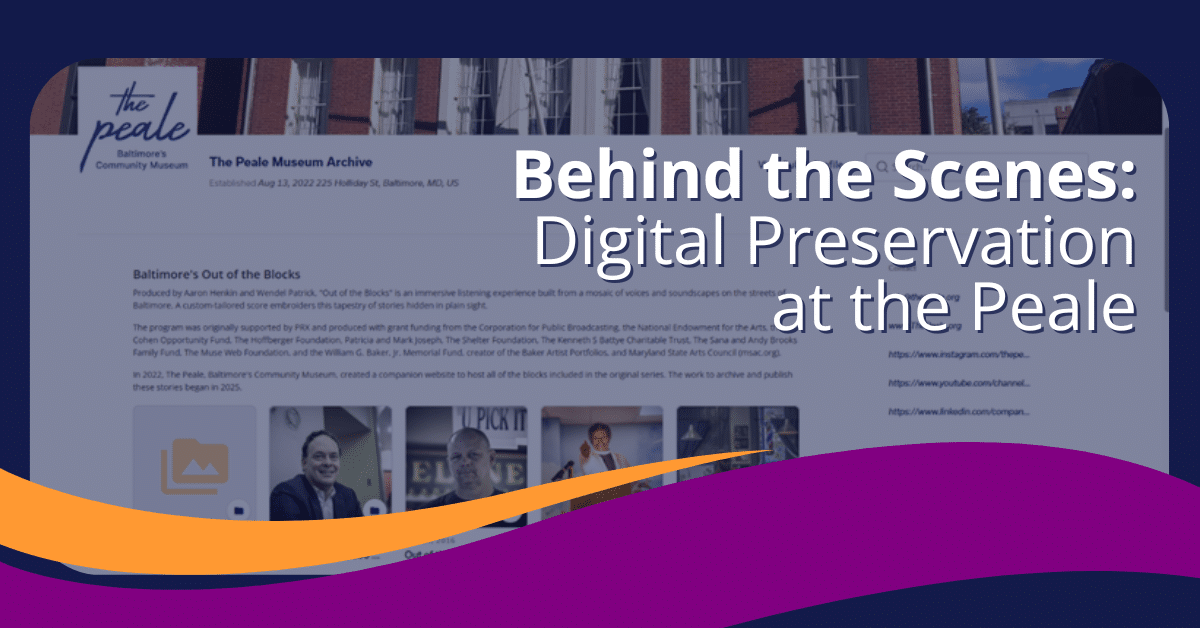

The Peale currently hosts this collection on its website, each interview matched with an appropriate image and PDF transcript and organized by the street they were hosted on. I, as an intern, was tasked with going through each interview, recording its details, and determining appropriate metadata tags and standards for the collection based on the details with the goal of tagging the interviews and uploading them to Permanent.org to make these newly-tagged interviews publicly available.

There are dozens upon dozens of OOTB interviews hosted by The Peale, and after surmising that downloading every interview’s files by hand would take hours, I instead wrote a script in the Microsoft PowerShell scripting language that would automatically download each file and organize the files by street into folders in a matter of seconds.

With that out of the way, I could focus instead on the meat of the project: the metadata.I would first listen to the interviews and write down their details (ID, interviewee name, etc.) in a shared Microsoft Excel file, one row for each interview, after which I would upload their image and audio files onto Piction.com, a content management system in the vein of Permanent.org, to determine the metadata. Then, I would upload the same files onto Permanent.org, where I would place interviews files into folders by street, then, within each street folder, create folders for each interview, which would contain the interview’s tagged image and audio files. I would finally completed my work on these interview files by attaching the metadata to each file as I had done on Piction, and The Peale would follow up by making the files publicly available, as seen here:

I was pleasantly surprised to see how intuitive Permanent was to use. Its clean interface makes it a breeze to navigate, and its feature set is broad enough to meet a wide array of metadata-creating needs, going so far as to include connectivity with Google Maps in a section for addresses. I also interacted frequently with their staff members, who were amicable, knowledgeable, and quick to respond, demonstrating a deep passion and understanding of their line of work. Unfortunately, I was unable to finish creating metadata for each interview, as it would have taken much more time than I initially expected, but I have greatly enjoyed using Permanent over the past three months in support of the community archives atThe Peale.

The workflow:

Heather Shelton: Now, back to the outcomes of the internship from The Peale’s point of view. Again, as a small museum with fewer resources, we greatly appreciated Nicolas’ time and enthusiasm to tackle this project. It was a small but important test case for us. The idea was to determine whether or not the process Nicolas used was sustainable for us in the long run. With Nicolas’ help, we figured out approximately how long it takes to ingest and add metadata to each story, so a “time per story” ratio that will help us establish legitimate time/cost estimates for future grant efforts and potential internships. We now know that it takes about one hour per story, if at least some of the metadata is known and the transcripts for the files have already been reviewed. The time per story could be 1-3 hours should all of the metadata need to be assembled and the transcriptions acquired and approved. That’s a significant difference in cost and one that may color how we prioritize various collections.

Nicolas also helped us think about which steps were redundant and could be eliminated, if possible. We’re still working mapping that out. We initially wanted to be sure that we had collections in multiple repositories, to safeguard against the catastrophic failure of one platform, whether it was a tech malfunction or the spontaneous collapse of a company. The mantra is “will it be easy to get your content out?” That assessment is still ongoing, but it’s wonderful to think that we have an objective view of what’s working and what could be improved! It’s just one step for us, but the internship helped us think about maximizing what we can do today rather than dreaming about the perfect scenario.